Strengthening your writing

Writing is the foundation of all your academic studies. Here you’ll find some advice on the basics of academic writing to help you become a better writer.

Good academic writing skills are essential to success at university. On this page you will find resources to help you write clearly, concisely and accurately.

Writing paragraphs

Paragraphs are the ‘building blocks’ of academic writing. Writing paragraphs well makes your writing clearer and will improve your grades.

If you are writing short answers, you might write just one paragraph. In an essay, report, or other assessment, you will write many paragraphs. No matter what you are writing, there are several key points to remember when you write a paragraph.

Focus each paragraph on one main idea

Paragraphs are not like bullet-point lists. A paragraph is like a ‘mini story’ that focuses on one main idea and provides evidence and examples to support that idea.

Make that idea obvious to the reader in the first one or two sentences

Start with a broader idea, followed by more specific detail. If you are writing an essay, your reader should be able to read the first few sentences of every paragraph and come away with a clear idea of your overall answer to the essay question.

In the rest of the paragraph, include detail about the idea

Explain, provide evidence for, or discuss the idea in the rest of the paragraph. What detail to include depends entirely on the assessment question you have been given, so read the question carefully to determine what kind of supporting detail you need. For example, you might include examples, explanation, expert opinion, theories, facts or statistics.

Reference information you are using to support your idea

If any of the supporting information has come from sources you have read, or heard in lectures, you must include a reference (citation).

Connect paragraphs to aid flow

Any piece of writing with a series of paragraphs, will need to have the paragraphs ordered so the main ideas form a clear logical sequence. Show the reader how the idea in each paragraph connects to the ideas which are before or after it. Include some words at the start of the paragraph that show the connection to the paragraph before. Or do this at the end of a paragraph to 'point forward' to the next one.

Honestly, there is no one right answer.

Most paragraphs are at least 3 or 4 sentences. They need to be that long to (a) present an idea and (b) explain or discuss it. If your paragraph seems to be too short, you have probably not provided enough information to explain or back up the point. Think about what other detail or evidence is needed.

On the other hand, if your paragraph is too long (for example, more than 250-300 words or one page), it’s likely you are trying to explain more than one idea – or simply have too much information about a single idea. Identify where you stopped talking about one main idea and moved on to your next main idea. Separate the second main idea into a second paragraph. Edit out any unnecessary explanation or examples if there is too much information.

Following the key points above will help you write clearer paragraphs, but there are ways of making them even better. Join a workshop or make an appointment with a Learning Advisor to find out how to make your writing flow and how to develop an argument. Also check out resources in the library that will help you learn how to write sentences that fit smoothly together (called 'flow' or coherence), and how to use a series of paragraphs to create an academic argument.

Have a look at our information on how to structure an essay or report.

Transition words or phrases help to clearly show the relationship between your ideas and guide the reader through your work. Use this guide to help you find useful transition signals for your writing.

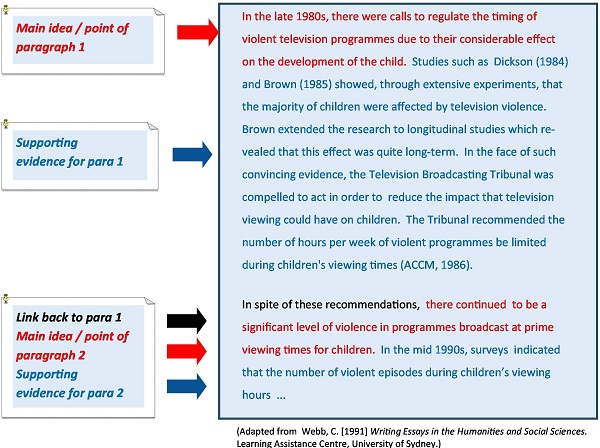

Look at how the writer of these paragraphs makes an overall point in each paragraph, uses detail to support the points, and links the two paragraphs.

Using sources

All academic writing draws on the ideas and findings of other researchers and writers. So, in most written assignments, you will need to refer to information you have found in sources.

Your writing needs to show the reader you have:

- read widely and understood the sources

- read the sources critically and developed your own point of view or conclusion about the information (we sometimes call this an academic argument or opinion)

- used the information as evidence to back up the points you have made in your writing.

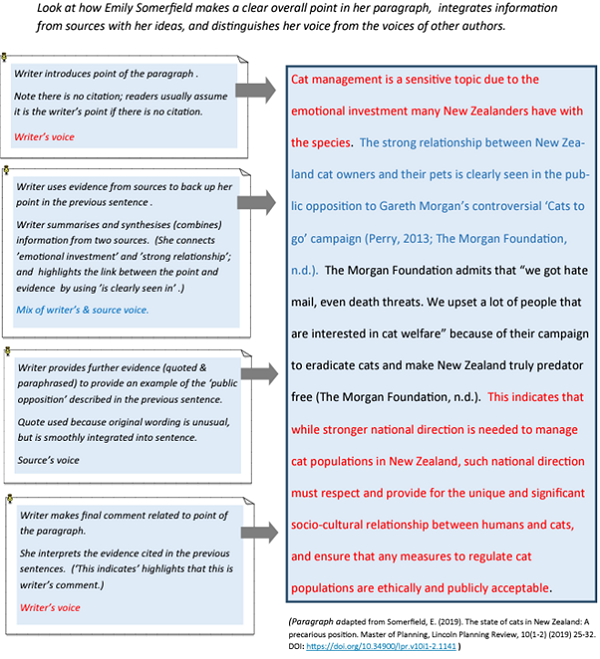

To smoothly integrate information from sources with your own ideas, show how and why the evidence supports your points, and clearly distinguish your ideas from the source information use the basic ‘building blocks’ of academic writing: points backed up with evidence (ie examples, research findings, expert opinion, theories, facts, statistics).

In each paragraph, introduce a key point that supports the overall theme of the entire piece of writing. Usually, the key point is obvious in the first few sentences. Then provide evidence to support and further develop the point. It is important to show the reader the connection between the evidence and your point, so discuss how the information supports your point or why the information is significant. Clearly reference to strengthen your work.

Help your reader to hear your voice by clearly distinguishing your points from the information you have found in sources. Making it clear what your ideas are and what are the ideas of others also helps you avoid plagiarism.

To make your voice clear:

- interpret or explain, the evidence

- point out connections between the pieces of evidence (eg common themes, logical links, gaps, agreement, disagreement)

- show your point of view, or opinion, about the evidence (eg comment on implications, significance, value)

- paraphrase or summarise much more often than quote.

Remember, when you use information you found somewhere else, you always need to provide an in-text citation and reference.

How do you decide whether to summarise, paraphrase or quote?

Summarise when you want to:

- Focus more on the meaning in a source than on the actual words used

- Provide an overview of a concept or topic

- Focus on only main ideas in a source

- Simplify and condense the information

- Present the information in your own writing style.

Paraphrase when you want to:

- Focus more on the meaning in a source than on the actual words used

- Include detailed information to explain points you are making

- Choose which details to emphasise

- Simplify and clarify the information

- Present the information in your own writing style.

Quote when you:

- Think it is important the reader knows exactly which words the original author used: eg

- to present a definition

- to highlight wording that is particularly significant or unusual

- to analyse or critique the wording used

- Want to provide authority from a recognised expert.

Here is a simple example:

|

Quote |

Paraphrase | Summary |

|

“Unless steps are taken to provide a predictable and stable energy supply in the face of growing demand, the nation may be in danger of sudden power losses or even extended blackouts, thus damaging our industrial and information-based economies. Building more gas-fired generation plants seems to be the best answer.” (Doe, 2007, p.37). |

Doe (2007) believes that we must construct additional power plants fuelled by natural gas if we are to have a reliable electricity supply during this period of increased usage. Without that, the country’s economic base (both industrial and information driven) may be damaged by lengthy blackouts or abrupt losses of power. | According to Doe (2007), gas-fuelled power plants are the key to the sustainable electricity supply required for economic development. |

(Adapted from Harris, R. A. (2017). Using sources effectively: Strengthening your writing and avoiding plagiarism (5th ed.). Routledge, pp. 84-85.)

What is it?

Paraphrasing is a process of rewriting information and ideas from a source in your own words, not simply combining blocks of information from different sources without making any of your own points.

Why paraphrase?

It is one way of using a source’s information to support points you make. You can include information from sources in your writing by paraphrasing, summarising or quoting. Paraphrasing demonstrates you understand an idea because you can restate it in your own words, style and sentence structure. Mixing large blocks of unchanged information into your work does not demonstrate understanding of your readings and may break rules around plagiarism.

How do I paraphrase?

First of all, get a good grasp of the meaning of the information before attempting to restate it.

Synonyms (words with similar meaning) definitely help in the paraphrasing process, but it is not enough just to replace a few words in the sentence. The whole sentence structure must be your original reformulation and the paraphrase written in your own style of writing; it has to sound like you.

Always cite where the idea came from.

Try one or more of these paraphrasing techniques:

- Reflect upon the source idea for a period of time without looking at the source. Once you have internalised its meaning, write the idea down in your own words, sentence structure and style, without referring back to the original. Check your paraphrase retains the meaning of the original.

- Explain the idea out loud, as though teaching it. Explaining an idea, as if to help a friend understand it, will cause you to re-present the information in a simplified way for the sake of your audience. Record yourself explaining aloud. Write down what you said. Formalise the wording.

- Identify critical v non-critical terms. Underline critical terms (technical or scientific words that cannot be changed) and non-critical words (general English words). Retain only critical terms when restating the idea in your own words, style and sentence structure. As you become more skilled at paraphrasing, you will retain fewer critical terms.

- Outline. For longer paraphrases, in the margin of the original paragraph, bullet point a few words that summarise of each sentence. Use these bulleted key words to re-formulate the original into your own paragraph construction, style and wording.

- Recycle. Take reading notes in paraphrased form. Paraphrase a second time when using the source in your writing (Be sure to label notes as “paraphrases” to distinguish these from notes that are quotations or your own comments.) Record where your paraphrase came from for the reference (citation).

Consider the following two attempts at paraphrasing.

|

Original source |

Paraphrase (incorrect) |

|

Unless steps are taken to provide a predictable and stable energy supply in the face of growing demand, the nation may be in danger of sudden power losses or even extended blackouts, thus damaging our industrial and information-based economies. Building more gas-fired generation plants seems to be the best answer. — John Doe, 2007 |

Doe (2007) recommended that the government take action to provide a predictable and stable energy supply because of constantly growing demand. Otherwise, we may be in danger of losing power or even experiencing extended blackouts. These circumstances could damage our industrial and information-based economy. He says that gas-fired plants appear to be the best answer. |

(Adapted from Harris, R. A. (2017). Using sources effectively: Strengthening your writing and avoiding plagiarism (5th ed.). Routledge, pp. 84-85.)

Even though an in-text citation is included, this is a poor paraphrase because:

✘ Too much of the original writer’s wording is used. Even using small groupings of exactly the same words, as in bold above, can be plagiarism. (We call this ‘patchwork paraphrasing’.)

✘ The sentence structure and word order of the original writer have not been changed enough.

| Original source | Paraphrase (correct) |

| Unless steps are taken to provide a predictable and stable energy supply in the face of growing demand, the nation may be in danger of sudden power losses or even extended blackouts, thus damaging our industrial and information-based economies. Building more gas-fired generation plants seems to be the best answer.—John Doe, 2007 |

Doe (2007) believes that we must construct additional power plants fuelled by natural gas if we are to have a reliable electricity supply during this period of increased usage. Without that, the country’s economic base (both industrial and information driven) may be damaged by lengthy blackouts or abrupt losses of power. |

(Adapted from Harris, R. A. (2017). Using sources effectively: Strengthening your writing and avoiding plagiarism (5th ed.). Routledge, pp. 84-85.)

This is a good paraphrase because …

✔ The writer restates the idea in their own style of writing. This shows their understanding of the material.

✔ Sentence structures have been changed from the original.

✔ Vocabulary has been changed (where possible).

✔ The original ideas are accurately represented and key detail is included.

✔ An in-text citation is included.

Remember that if your writing does not look consistent, your marker will suspect plagiarism.

Using paraphrases and summaries

Use paraphrases and summaries to include information and ideas from a source in your own words.

Make sure you:

- use the paraphrase/summary to support the points you are making (i.e. don’t simply report information)

- use your own words and style

- include a citation

Citing paraphrases and summaries

Each time you use information from a source, you need to include an in-text citation (author’s family name, date) to tell the reader where you found that information.

Where you put the in-text citation depends on how you have used the information. Here are some common examples of how summaries and paraphrases are used and cited.

When you want to:

- Focus on the author/s of the source.

For example, you want to report detail of a study’s findings or ideas; compare different studies or points of view; comment on/evaluate the information in a source; or highlight an author because they are a recognised expert.

Include the author’s name and the date in the body of your sentence.

Bladh (2019) draws a distinction between ‘exciting’ and ‘boring’ products, where exciting products allow users to innovate with their lives while boring products are simply tools in existing practices.

Bergin and Kimberley (2014) found that regeneration of totara (Podocarpus totara) in the presence of grazing was more prevalent on steeper slopes. This is consistent with the findings in Forbes et al. (2021), which also noted the correlation between … .

- Focus on the information from the source.

For example, you want to present a fact; show what is currently known.

Include the author’s name and the date in parentheses at the end of your sentence.

The capacity of the electricity distribution network to deliver electricity for vehicle charging is not evenly distributed (Page et al., 2020).

If you are making more than one point in the sentence, you will need two citations, with each citation close to the point it supports.

Most indigenous species rely on seed dispersal by wind or birds from remnant patches of existing vegetation (Wilson et al., 2017), with the dispersal distance of propagules from indigenous New Zealand tree species generally limited to a few hundred metres (Canham et al., 2014; Wotton & Kelly, 2012)

- Support a point with multiple sources.

For example, introduce a point generally instead of, or before, examining it in detail; show there is extensive evidence to support the point; show consensus/agreement.

Include the author’s name and the date for each source in parentheses at the end of your sentence. Separate each source with a semicolon.

Roads also bisect human and animal communities resulting in community severance and leading to negative impacts in terms of safety and community cohesion (Anciaes et al., 2016; Appleyard, 1980; Boniface et al., 2015).

The general consensus in the literature is that relying on natural regeneration is the preferred and most economically viable method for establishing permanent indigenous forest, particularly on marginal hill country (Bergin, 2012; Bergin & Gea, 2005; Carswell et al., 2012; Chazdon, 2017; Davis et al., 2009; Scion, 2019).

- Provide extensive detail about one particular source (over several sentences)

For example, explain or comment on a study or idea in detail throughout a paragraph.

Include the author’s name and date the first time the source is mentioned.

In the sentences that follow, make it clear where the information has come from. You may not need a full citation in every sentence, as long as there could be no confusion with other sources cited in your writing. (For example, you can omit the date after the first citation if it is clear what the source is.)

You can remind the reader throughout the paragraph you are still referring to the same source by repeating the author’s name in the sentence or using the phrase ‘the author’.

The differences between the scales are significant (Kuenapas & Johnson, 2017). According to Kuenapas and Johnson, the … is more likely to … . The authors argued that …

More recently, Carruthers and Wilson (2015) examined the use of new technologies in ... . They concluded that … Carruthers and Wilson also point out ...

Using quotes

Use quotes to include the original source’s exact words.

Make sure you:

- introduce the quote and/or specifically link it to the point you are making

- do not use a quote that simply repeats what you have already written in your own words

- fit the quote smoothly into the structure of your sentence(s)

- include a citation

Citing quotes

Each time you use quotes from a source, you need to include an in-text citation (author’s family name, date, page number) to tell the reader where you found that information.

Here are some common examples of how quotes are used and cited.

- Short Quotes (Less than 40 words)

Put the quoted words in quotation marks (“….” or ‘ …’. Include the author’s name, the date, and the page number in the citation.

If the author’s name is included as part of the sentence, place the citation (year and page number) in parentheses immediately after the author’s name.

Kester (2018, p. 210) notes that people often “buy a car with the specifications (range and towing power) for those few trips a year to holiday destinations, instead of a smaller and lighter car for their daily routines”.

If the author’s name is not part of the sentence, place the citation (name, date, page number) in parentheses immediately after the quote.

Contemporary forms of drive tourism must “retain their sense of fun, flexibility and freedom” (Fjelstul & Fyall, 2015, p. 469) as they transition to more sustainable models.

Perhaps most interesting from the perspective of the social science of tourism, is the way in which incorporating vehicles into the electricity grid might challenge “the traditional image of the automobile, its design, purpose, and meaning” (Wentland, 2016, p. 286).

- Long Quotes (40 or more words)

Begin the quote on a new line and indent. No quotation marks are needed.

If the author’s name is included in the sentence introducing the quote, include the date in parentheses immediately after the author’s name, and the page number in parentheses immediately following the quote block.

As car use and leisure travel grew, the association between them was cemented, as Ivory and Genus (2011) explain:

The car, from its establishment at the end of the nineteenth century, has been associated with the notion of travel for pleasure. Travel for pleasure was a critical aspect of how the car was understood and consumed and a key element in emerging car culture. (p. 1114)

If the author is NOT named in the sentence introducing the quote, include the author’s name, date, and page numbers in parentheses immediately following the quote block.

As car use and leisure travel grew, the association between them was cemented:

The car, from its establishment at the end of the nineteenth century, has been associated with the notion of travel for pleasure. Travel for pleasure was a critical aspect of how the car was understood and consumed and a key element in emerging car culture. (Ivory & Genus, 2010, p. 1114)

- Changing the words of a quote

Usually, you use the original words when you quote. There are some exceptions:

If there are errors in the original work, leave those errors in the quote, but add [sic] to let the reader know there is an error in the original.

Including new technologies “enhances energy efficiency but reducts [sic] cost effectiveness” (Simons, 2018, p. 79).

If you need to change the wording of the quote to make its meaning clearer or make it fit smoothly into your sentence, enclose the changes in [ ] to show that they are not part of the original quote.

Cars are widely seen as “[enabling] the car driver to travel at speed, at any time in any direction” (Urry, 2000, p. 59).

If you need to omit some wording of the quote to make its meaning clearer use ellipsis (i.e. 3 full stops) to show there are missing words.

As Ivory and Genus (2010) explain:

The car, from its establishment at the end of the nineteenth century, has been associated with the notion of travel for pleasure. … Travel for pleasure was a critical aspect of how the car was understood and consumed and a key element in emerging car culture. (p. 1114)

References

Fitt, H. (2022). Boring and inadequate? A literature review considering the use of electric vehicles in drive tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 25:12, 1920-1946. https:// doi.org/ 10.1080/13683500.2021.1937074

Pedley, D. (2022). Natural regeneration of woody vegetation in pastoral hill country: A case study of Oashore Station, Banks Peninsula. [Masters Thesis, Lincoln University]. Research@Lincoln. https://hdl.handle.net/10182/15025

Polishing your language

Sentence structure - Using different types of sentences allows you to highlight different relationships between ideas and to add variety to your writing. This tip sheet on sentence structure is designed to help you to construct sentences accurately, so that your meaning is clear.

Punctuation basics - Punctuation helps the reader to understand the meaning of your sentences. The helpful punctuation basics sheet has information about some of the basics of punctuation, especially aspects which are important in academic writing.

Tense use in academic writing - This summary of tense use in academic writing covers the most commonly used tenses in undergraduate academic writing, with lots of examples and explanations of their uses. Tense use in academic writing...for writing about research provides more detail about common uses of tense in writing up research.

Bonus resource, academic phrasebook - This Academic Phrasebank is an excellent resource that provides a wide range of phrases commonly used in research writing (Collated by University of Manchester)

Revising and editing

Revising, editing and proofreading are essential stages in the writing process, not just an ‘optional extra’ to be done only when you have time. It's not easy, but there are strategies you can use that will help to make your revising more effective:

- After writing your draft, leave it for a few days before revising, so you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Get feedback from someone else on the general clarity and sense of your writing.

- Don’t try to check for everything at once. Use a revision checklist to identify and prioritise the features you want to concentrate on; then read through your paper for one feature at a time. Using a checklist is one way to edit more effectively – even professional writers use them. You could use either this essay checklist or this report checklist to ask yourself about the content, structure, and style of your work. Even better, adapt one of the checklists to suit your own needs.

- Adapting a check list allows you to build up your own personal revision checklist, particularly for editing and proof-reading at the sentence and word level (ie for identifying grammar, spelling and punctuation errors).

Identify the errors you commonly make. Use the marker's comments on completed assessments or ask for feedback on your writing from a friend or a Learning Advisor.

Rank the errors so that you can concentrate on the types that are most common for you and/or those that are most serious. Find out how to correct the errors. Talk to a Learning Advisor about this or use a basic self-help grammar book. These will have specific strategies that you can use to find and fix the errors in your writing.

- Once you are ready to check your paper at the sentence and word level, print it out and use a piece of paper to hide most of the work so you are forced to read one line or sentence at a time. Also, try reading your paper aloud, slowly.

- Get into the habit of using a dictionary, a grammar book, or a style guide whenever in doubt.

- Ensure your spell check is set to NZ (or UK) spelling as that is the convention in New Zealand. Be careful with MSWord Editor and any apps that provide grammar and writing advice. Remember the suggestions are not fool proof and you need to decide whether to make changes or ignore them.

Get Individual Advice

Talk to a learning advisor or attend one of our workshops for help with your study.